exhibition

2.2.22 – 31.3.22

Cosima Hawemann’s chosen title for this exhibition is as provocative as it is evocative. She rarely provides a prescriptive artist statement about her work, preferring instead to give a few key concepts and leaving the interpretation to the viewer, knowing that the interpretation will be influenced by the viewer’s own knowledge, memories, and belief systems. The absence of an artist’s statement (the viewer’s security blanket) can make for an intriguing – and at times disturbing – experience as one gazes upon her mysterious and often untitled scenes.

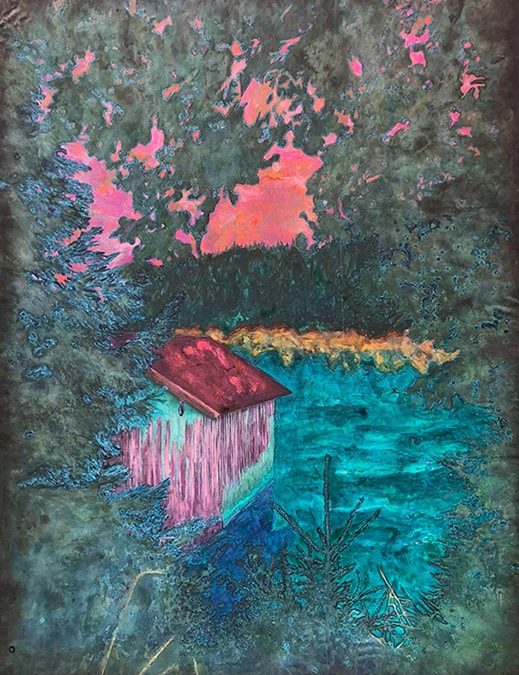

“Landscreen” suggests a collision of the naturalistic and technological worlds, which is, indeed, the case. Hawemann’s starting point for each work is a digital image she takes of her surroundings. From there, the image is either printed directly onto paper or transferred onto polyester screen mesh using a photographic process involving a negative transparency the original photograph and light-sensitive emulsion.

At this point traditional painting techniques reassert themselves, but even here, Hawemann’s otherworldly colouring recalls celluloid or computer-generated colour negatives, or the holographic images we see on the back of our eyelids after looking at a strong light. This allusion to the photographic process reinforces the mediating power of the screens which have come to dominate our lives and shape our ways of seeing and interacting with the world around us.

Hawemann has been investigating memory in her work for many years. Could, then, the technological screens she uses prior to the act of painting also stand for the internal mind-screen onto which we project our memories? As to the question of fidelity, what if our memories degrade in the same way as JPGs do when they are repeatedly opened and saved?

It begs the question of how reliable our memories really are and whether we can accurately remember what we see, or whether our mind’s own processing methods act to distort and recolour elements of each captured image/memory. Just as our memories don’t perfectly capture every detail of a scene, Hawemann shifts between showing detail losses and clear focus within the same painting. The paintings, then, can be seen to stand for the behaviour of our activated memories. Thus, she provokes in the viewer feelings similar to the tension and frustration that we experience as we struggle to fill in missing information and sharpen the blurred edges of our recalled memories. We know it’s there somewhere, if only we could remember who, what, where, when … We shrug off our imperfect recall in the hope it will return later, but our failure of perfect recall continues to prick our sense of self-mastery as well as our pride.

A recent development in Hawemann’s work is the use of polyester screen mesh used in a double layer as a painting support. When painted upon, the transparency of the fabric creates a moiré effect which mimics the kaleidoscopic sensation we’ve all experienced when trying to hold a memory in our mind’s eye: As soon we focus our attention on one area, the image shifts and distorts, edges blur, warp or disappear, colours meld and change. The image/memory can never be completely frozen and forensically examined. If that is the case, can truth ever be determined based on our memory of what we have seen and are able to recall?

Further, the material behaviour of this new medium lends some qualities to the aesthetic experience that mirror viewing a screen-based image. The semi-transparency of the fabric allows for a certain amount of ambient backlighting, creating a soft, screen-like “glow”; the brighter the ambient light, the stronger the effect. Where traditional paintings are only able to reflect light due to their complete opacity, Hawemann’s polyester screen mesh works allow for both reflected and transmitted light. These works are not backed by board and may therefore change in luminance and colour tone depending on the colour of the wall they are hung on. A white wall will provide maximum luminance, while a dark wall will echo the dark mode on a mobile phone. Coloured walls may change how the painting’s colours are perceived (if this effect is considered undesirable, a white backing board will limit the painting to its neutral state).

On hearing of Hawemann’s choice of “Landscreen” for the exhibition title, it conjured for me images of tourists happily snapping away on their phones as they passed each vista on their itinerary. Interestingly, there is often evidence of a human presence, despite the absence of a figure, in Hawemann’s work – huts, boats, felled trees in a wood, a domesticated horse – but the scenes are imbued with an eery stillness suggesting desertion. Such is the behaviour of many tourists: they come briefly, take numerous photos, then desert that scene for the next. Is the only experiential impression of that moment limited to what is recorded on their camera roll? If they spend more time looking at their screens than real life, will their memory function without digital images aiding recall; or has the camera roll and its offshoots like Instagram already made the mind-memory redundant?

It is not for Hawemann to answer those questions, but for us. Through her hybrid approach, she has transformed the age-old and seemingly innocuous genre of landscape painting into a profoundly philosophical and sensitive investigation of the 21st century’s Zeitgeist. Throughout history the available technology has shaped society and its cultural production, as it does today. In blending the old and new, the tested and experimental, Hawemann holds up a painterly mirror so that we may see ourselves more clearly, while reminding us that all may not be as it appears or as it is remembered.

Now online: https://www.galeriezadra.com/exhibition/cosima-hawemann-landscreen

Abbildung: Cosima Hawemann, Bootshaus, acrylic and photographic emulsion on polyester screen mesh, 120 x 90 cm